A Convenient Expression for Packed Circle Radius

When you develop a solver for the Tammes problem you're usually concerned with distributing points evenly on the sphere, ensuring they are equidistant from each other. The radius of the circles you place at those points is generally not considered:

There are known solutions for a given number of circles but there is no known solution for any number of points. Relaxation can be used in the general case.

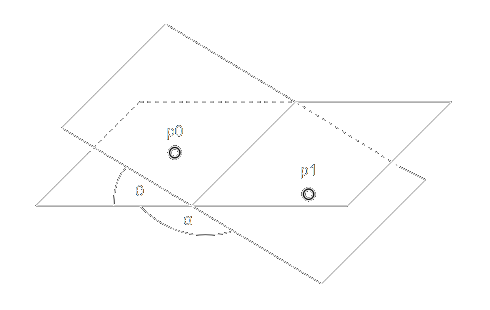

Once the unit sphere is packed with circles, finding the radius can start with two circles and the planes they lie within:

If the circle center points \(p_0\) and \(p_1\) are on the unit sphere, they can also be considered the normals of the planes they lie within. The acute angle \(\theta\) between these two planes is called the dihedral angle and is easily calculated as:

\[\theta = acos(p_0 \cdot p_1)\]

The obtuse angle, \(\alpha\), is called the anhedral angle and is thus:

\[\alpha = \pi - \theta\]

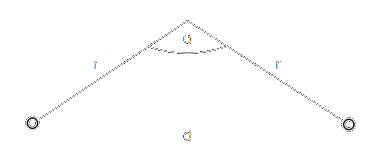

The adjacent/opposite sides of the triangle formed by the two planes and the line joining \(p_0\) and \(p_1\) will be the same size and can be considered the desired circle radius:

Using the Law of Cosines an expression for \(d\) and then \(r\), can quickly be attained:

\[d^2 = r^2 + r^2 - 2r^2cos(\alpha)\]

\[d^2 = 2r^2(1 - cos(\alpha))\]

\[r = \sqrt{\frac{d^2}{2(1 - cos(\alpha))}}\]

This works well enough to get the radius you want but the overuse of transcendentals feels like it can be squeezed some more. Following the Law of Sines makes things even worse but there's a clue in the \(cos(\alpha)\) term which expands to:

\[cos(\pi - \theta)\]

This can be reduced using a common trigonometric identity:

\[cos(\pi - \theta) = cos(\pi)cos(\theta) + sin(\pi)sin(\theta)\]

Given that \(cos(\pi)=-1\), \(sin(\pi)=0\) and \(\theta=acos(p_0 \cdot p_1)\), this immediately reduces to:

\[cos(\pi - \theta) = -(p_0 \cdot p_1)\]

Leaving the final substitution:

\[r = \sqrt{\frac{d^2}{2(p_0 \cdot p_1 + 1)}}\]